A Data-Driven Look at Europe’s Succession Crisis

A map of where Europe’s succession wave is hitting hardest - and what it means for SME owners planning their exit.

Across Europe, a quiet shift is underway. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) make up over 99% of all businesses in the EU and are consistently described by the European Commission as the “backbone” of the economy.

At the same time, a large share of SME owners are now over 55 and starting to think about retirement. That combination - lots of small businesses, plus aging owners - is what sits behind the so-called “succession crisis”.

1. What the Europe-wide numbers say

The EU and partner organisations have been tracking business transfers for years. The picture that emerges:

- Around 450,000 firms are transferred every year in Europe, involving roughly 2 million employees.

- Each year, about 150,000 businesses are at risk of not finding a successor.

That’s the baseline: a large, ongoing flow of ownership changes, with a meaningful chunk at risk of simply failing.

Layer on demographics and the story gets sharper.

2. The “red zone”: countries with intense succession pressure

These are markets where you see both a high share of family/owner-led businesses and visible succession bottlenecks.

Germany: high volumes, aging owners

Germany has about 3.8 million SMEs. KfW’s latest status report estimates that around 626,000 of them plan a transfer between 2023 and 2027 – roughly one in six.

Roughly 30% of SME owners are already over 60, and KfW openly warns that a shortage of successors is likely to worsen.

For founders, the message is simple: there will be a lot of sellers and not enough obvious buyers, especially in traditional sectors.

Italy: family-heavy economy, fragile generational hand-overs

In Italy, SMEs account for over 99% of companies and nearly 78% of the workforce.

Studies on family firms show that:

- Family businesses represent a large majority of Italian companies, and

- Many fail to make it beyond the second or third generation – one paper suggests over 70% do not survive the second generation, and another notes only ~4% reach the fourth.

That doesn’t mean every Italian company is about to be sold. But structurally, a big share of the country’s productive base is family-owned, with fragile succession paths.

Central & Eastern Europe: first big transfer wave

In CEE, the current succession wave is often the first real transfer since the early 1990s.

- In the Czech Republic, family businesses are estimated to generate over 55% of GDP and employ about 2 million people. Up to two-thirds lack a clear succession plan.

- In Hungary and parts of the region, a significant share of founders are already beyond normal retirement age, while governance and tax structures for transfers are still maturing.

- Romania and Bulgaria are seeing the first large cohort of post-1990 founders approach exit, often with limited internal successors and under-developed markets for smaller M&A deals.

Here, the risk is more about lack of process and infrastructure than lack of buyers. Many solid companies could change hands if the process were easier to run.

Greece: many family firms, weak options

Across Southern Europe, family firms dominate. A major European study suggests that in Spain, Italy and France, and by extension similar economies like Greece, more than 80% of businesses are family-owned. (BNP Paribas Wealth Management)

Greece adds extra complexity: long-standing family ownership, heavy reliance on banks, and a limited mid-market M&A ecosystem. That combination means many founders have few obvious paths between “keep running it forever” and “quietly wind it down”.

3. The “orange zone”: succession pressure, but slightly better prepared

Some countries are in better structural shape but still face very real succession waves.

France

France combines a high share of family firms with an aging owner base:

- European family business research puts family firms at more than 80% of all businesses in France.

- National and EU reports point to hundreds of thousands of owners expected to retire before 2030, with tax and governance rules still catching up to that reality.

The French system has more developed finance and advisory infrastructure than many CEE markets, but the volume of transitions is still material.

Spain

For Spain, new surveys suggest that around 35% of family offices expect a generational shift in the next 10 years – a good proxy for larger family-owned groups.

Succession tax reforms have eased some tax pressure, but planning and governance remain uneven.

Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands

- Austria: a high share of SMEs with owners over 55 and a need for structured transition planning by 2030.

- Switzerland: many high-value industrial and services family firms, with owners increasingly looking at external investors or partial exits as an alternative to full family succession.

- Netherlands & Belgium: more diversified economies and stronger institutional investors, but still dominated by SMEs and family firms, with the same demographic clock ticking.

These are not “crisis” markets in the same way as parts of CEE, but the flow of transfers and partial exits is steady and growing.

4. The “yellow zone”: emerging succession opportunities

A few markets look comparatively better prepared, but still present meaningful business-sale potential.

United Kingdom

The UK has a very mature SME and M&A ecosystem:

- SMEs make up over 99% of all firms and employ around 16–17 million people.

- The advisory and private equity markets are deeper than in most of Europe.

The UK is less likely to see mass closures purely because of a lack of buyers – but it will still see a large volume of baby-boomer founders exiting over the next decade, especially in sectors like professional services, local trades and IT.

Nordics

Countries like Sweden, Denmark and Finland have smaller populations but high levels of digital readiness and strong buyer ecosystems. They may not face a “crisis” in the same sense, but they are fertile ground for consolidation plays in software, services and specialist manufacturing.

5. Why traditional investment banks and brokers struggle with this wave

On paper, banks and classic corporate finance boutiques should be natural candidates to handle this. In practice, the economics don’t work for most small and mid-sized owners.

A few hard constraints:

- Deal size vs. effort

- A mid-market investment bank might focus on deals €50m+.

- Many succession cases sit in the €3–20m enterprise value range – sometimes lower.

- Running a full, global buyer process manually (research, outreach, management of offers) for a €7m industrial services firm looks like “too much work for too little fee” in their model.

- Retainers and friction

- Banks and many traditional brokers rely on monthly retainers plus a success fee to cover the heavy lifting.

- For a retiring founder, paying €5–15k a month for 6–12 months before knowing if a deal will happen is often a non-starter.

- Limited buyer mapping in practice

- A human-only team can realistically research and contact dozens of buyers – maybe a hundred – without burning out.

- The real buyer universe for a niche SaaS, a dental roll-up, or a specialised logistics firm might be hundreds or thousands of potential acquirers across Europe, not 15 local names.

- Broker model is mostly passive

- Most business brokers list the company on a marketplace, send a short PDF to their existing list, and see who responds.

- There is rarely a deep, data-driven search for the “best owner” of the business – just the “first buyer who shows up and can pay.”

So you end up in a dead zone:

- Too small and manual for banks

- Too complex and strategic for a pure listing broker

- Too important to leave to chance for the owner

This is exactly the gap an AI-native advisory model is designed to fill.

6. How an AI-native M&A advisory model can actually help

An AI-native advisory model starts from a simple principle: use technology to do the heavy lifting, so experienced advisors can focus on the parts that close deals.

Three areas where an AI-native M&A advisory can support:

a) Mapping and connecting to an extensive buyer universe, not just the obvious names

An AI-native model can scan a proprietary database of millions of companies globally and filter them by:

- Past acquisition behaviour

- Sector, sub-sector and even synergies based on products, target markets, USPs etc.

- Size and growth

- Geography and strategic fit

The result is a shortlist of hundreds of plausible buyers, not a random long list:

- Strategics consolidating the space

- Private equity with active “roll-up” theses

- Regional groups looking for their first foothold in that country or industry

According to public material, this kind of platform can identify hundreds of synergetic buyers in under a week, rather than months of manual desk research.

b) Sharper materials and smoother due diligence

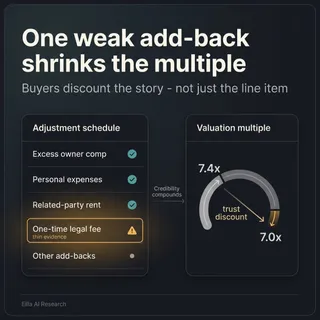

Most buyers don’t walk away because the core business is bad. They walk away because:

- The story is unclear

- The numbers are messy

- The information arrives late or contradicts earlier claims

An AI-enabled team can:

- Turn raw data, exports and notes into a clear, consistent information pack that explains what the business does, how it makes money, and where the risks are.

- Help structure and maintain a data room that stays up to date as questions come in.

- Use automation to track questions, draft responses, and keep information aligned across all buyers.

For an owner, that means:

- Fewer surprises in due diligence

- Less time digging for the same numbers again and again

- A higher chance that serious buyers stay engaged to the finish line

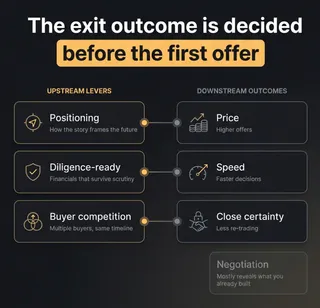

c) Running a competitive process with success-fee only model

Because research, document drafting and buyer discovery are automated, the human advisory team can focus on:

- Positioning the company clearly

- Running a structured outreach process

- Managing conversations and bids

- Creating real competitive tension between buyers

With automation doing the heavy lifting, the model can work on a success-fee-only basis with no upfront retainers and still be sustainable.

For the owner, this matters:

- You can run a proper process without paying large fees before anything happens.

- You are not limited to whoever happens to see your listing.

- You are more likely to see multiple offers within weeks, not just one offer after 3 to 6 months of waiting.

sense for a mid-sized or smaller exit.

The bottom line

The numbers are clear:

- Over 99% of EU businesses are SMEs.

- In markets like Germany, Italy, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Spain and other European countries, demographic and ownership trends mean the pace of succession events is only going to increase.

Whether that turns into a crisis of closures or a wave of successful transitions depends less on the willingness of founders to sell, and more on whether practical, scalable processes exist to help them find the right buyers and get deals done.

That’s exactly the gap AI-native advisory models are trying to close. Book a meeting with our team today and see how we can support your exit.

Are you considering an exit?

Meet one of our M&A advisors and find out how our AI-native process can work for you.