Selling an SMB: A Step-by-Step M&A Process from Preparation to Close

A practical guide to running a competitive SMB sale process - from preparation and positioning to diligence and closing - so you protect your valuation, create competitive tension and avoid the deal-killers that derail most exits.

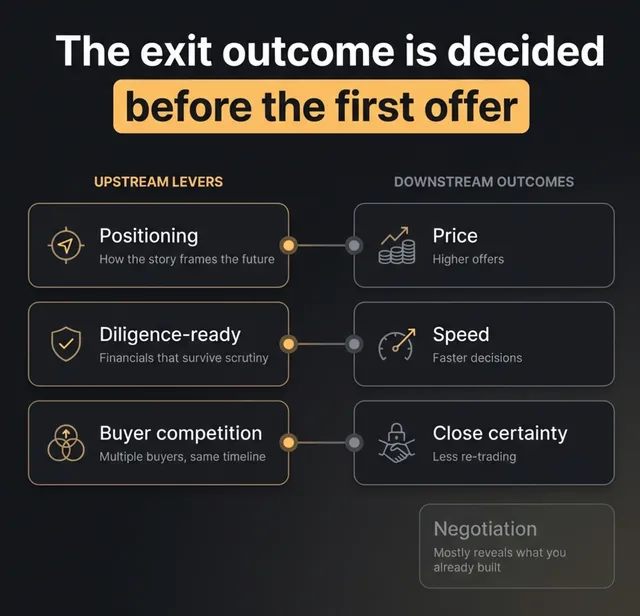

Most founders picture selling their company as a negotiation. Two parties, a price, a handshake. In practice, an SMB sale is a three-to-nine-month project with dozens of moving parts, and the outcome is shaped far more by process design than by any single conversation at the table.

Selling a small or mid-sized business typically takes 3 to 6 months from go-to-market to close, and involves five core phases: preparation, go-to-market and buyer outreach, managing offers and competitive dynamics, due diligence, and closing. The most consequential decisions happen in the first two phases - before a buyer ever submits an offer - because that's where you build (or fail to build) the leverage that protects your price later.

This guide walks through each phase, what actually happens during it, where deals most commonly break down, and what you can do to stay ahead of the process rather than react to it.

Why the narrative you build matters more than the numbers you show

Here's something that surprises most first-time sellers: the financial model isn't what sells your company. The story around the financial model is.

Every serious buyer will rebuild your numbers from scratch during diligence. They'll normalize your EBITDA, stress-test your revenue mix, and benchmark your margins against comparable businesses. You can't control that - it's their job. What you can control is the frame they use to interpret those numbers.

Two companies with identical financials can receive meaningfully different valuations depending on how the business is positioned. A digital marketing agency doing EUR 1.5M in EBITDA will attract a different buyer universe - and a different multiple range - depending on whether it's presented as "a profitable agency with good clients" or "a recurring-revenue platform with 90%+ retention, vertical specialization in healthcare, and a playbook that's been replicated across three markets."

Same numbers. Different narrative. Different outcome.

This is why preparation isn't just about cleaning up your books (though that matters enormously). It's about understanding what makes your business valuable to a buyer and building the materials, the data room, and the positioning around that thesis before you go to market.

How to prepare your business for sale (and why most sellers start too late)

Preparation is the phase that separates clean exits from painful ones. According to a 2025 study by BNY Wealth, 38% of business owners who completed a sale wished they had allowed more time for sale-related tasks, and 36% wished they had ensured better documentation and financial records before starting.

The reason is straightforward: anything a buyer discovers during diligence that you haven't already anticipated becomes leverage against you. Preparation is about removing that leverage before the process starts.

Financial readiness: defend your EBITDA before someone attacks it

The single most important number in any SMB transaction is adjusted EBITDA - your earnings after normalizing for owner compensation, one-time expenses, and non-recurring items. This is the number that gets multiplied by your valuation multiple to produce a purchase price.

The problem is that "adjusted" is where most disputes happen. In industry reports, deals that fell apart after a letter of intent was signed, quality-of-earnings discrepancies accounted for roughly 1 in 5 of failures. In practical terms, that means a buyer's accountants looked at the seller's EBITDA, rebuilt it from the general ledger, and arrived at a materially different number.

What drives this gap in SMB deals specifically:

- Personal expenses running through the business. Owner vehicles, family payroll, personal travel. These are theoretically "add-backs," but if they're pervasive and poorly documented, buyers and their lenders discount them rather than accept them at face value.

- Revenue recognition that doesn't hold up. Recognizing project revenue before delivery, booking annual contracts as lump sums, or inconsistently timing invoice recognition. These create a picture of earnings that shifts under scrutiny.

- "Non-recurring" expenses that keep recurring. If you've had a "one-time" restructuring charge in three of the last four years, a buyer will treat it as a recurring cost.

The fix isn't complicated, but it takes time: get your financials into shape before you plan to go to market. Ideally, have a third-party quality-of-earnings review done on your own terms, before a buyer commissions one designed to find problems.

Building the information package: your business through a buyer's eyes

Before a single buyer sees your company, you need a set of materials that tells a coherent story. This typically includes a confidential information memorandum (CIM) - a detailed document covering your business model, financial performance, market position, growth levers, team, key risks etc.

The CIM isn't a sales brochure. It's a structured argument for why your business is worth what you're asking, supported by data. The best CIMs anticipate buyer questions rather than dodge them. If you have customer concentration, address it with retention data and pipeline diversification. If your margins compressed last year, explain why and show the trajectory.

Alongside the CIM, you'll prepare a data room - a secure online repository with financial statements, tax returns, contracts, employee information and operational documents. The quality of your data room directly affects how long diligence takes and how much friction it creates. A well-organized data room with clean, complete documentation signals to buyers that the business is well-run. A messy one signals the opposite - and invites deeper scrutiny.

Aligning stakeholders before you go to market

If you have co-founders, a board, a spouse with a stake in the outcome, or key employees whose retention matters to a buyer - align them before the process starts. Seller-side breakdowns account for around 10-15% of DD deal failures in industry reports and many of these trace back to stakeholders who weren't genuinely bought in from the beginning.

This means having honest conversations about price expectations, deal structure flexibility, post-close roles, and timeline. It also means being honest with yourself about whether you're actually ready to sell - "testing the market" without commitment wastes months and burns credibility with serious buyers.

How to take your company to market: competitive process vs. bilateral negotiation

This is the single highest-leverage decision in the entire process and it's the one most SMB owners get wrong.

A bilateral negotiation means you're talking to one buyer. Maybe they approached you, maybe you know them, maybe it feels easier. A competitive process means you're approaching multiple qualified buyers simultaneously, creating a structured timeline, and using competitive tension to drive better terms.

The instinct for many founders is to go bilateral. It feels faster, simpler, more discreet. But here's what bilateral negotiation actually means in practice: you have no leverage. If the buyer knows they're the only one at the table, every diligence finding becomes a reason to renegotiate. Every delay costs you and only you. The buyer sets the pace, because they can.

In a competitive process, the dynamics invert. When a buyer knows other serious parties are evaluating the same opportunity on a similar timeline, several things happen: they move faster (because delay means losing the deal), they bid higher (because they're pricing against competition, not just against their internal model), and they're less aggressive on re-trading during diligence (because you have alternatives).

The data supports this. Industry benchmarks consistently show that competitive tension forming within the first two weeks of a process correlates with materially better outcomes. The reason is structural: early competitive tension forces buyers to put forward their best offer upfront rather than anchor low and negotiate up.

How a competitive process actually works for SMBs

Running a competitive process looks like this:

- Build a targeted buyer universe. Identify the best fit potential acquirers - a mix of strategic buyers (companies in your space or adjacent spaces) and financial buyers (private equity firms, family offices, search funds). The goal is to have a broad enough universe of high fit buyers that could be interested in your business which increases your chances of selling.

- Buyer outreach. Approach buyers under NDA with a teaser document (anonymous summary) and then the full CIM for those who sign. This happens over a defined 2-to-3-week window.

- Management presentations and commercial due diligence. Buyers who are interested after reviewing the CIM will request a management presentation - typically a 60-to-90-minute session where they meet the founder, ask questions about the business, and get a feel for the opportunity. Following this, they'll go through a round of additional questions covering customers, revenue quality, operations, growth assumptions etc. This is what's known as commercial due diligence - and it's where serious buyers separate themselves from casual interest.

- Non-binding offers. On the back of their commercial due diligence, buyers who want to move forward submit non-binding offers - typically including a valuation range, proposed deal structure, key conditions and a timeline for completion.

- Selection and exclusivity. You review the offers and select which party (or parties) you want to continue the process with. At this stage, you may negotiate exclusivity with one buyer - giving them a defined window to complete confirmatory due diligence and move toward a binding agreement.

The entire go-to-market phase - from first outreach to entering exclusivity - typically takes 4 to 8 weeks in an AI-native process.

Why buyer outreach matters more for SMBs than most founders realise

In large-cap M&A, the buyer universe is relatively obvious. There are a handful of known acquirers, everyone knows who they are, and the advisor's job is mostly about managing relationships and running a tight process. In the SMB world, it's the opposite. The pool of potential strategic buyers is enormous - but scattered, opaque, and largely unknown to the seller.

A €10m revenue digital agency, for example, could be a fit for a larger marketing group looking to add a new capability, a private equity-backed platform doing a roll-up in the same vertical, a SaaS company looking to bolt on a services arm, or even a corporate in a completely different industry that's trying to bring a function in-house. Each of these buyers has a different strategic rationale, a different willingness to pay, and a different view of what the company is worth to them. The problem is that most founders - and even many traditional advisors - don't know which of these buyers exist, let alone what their acquisition strategy looks like.

This is where breadth of outreach becomes a genuine value driver. The more high-fit buyers you put the opportunity in front of, the more likely you are to find the one whose strategy happens to align perfectly with what you've built - and that alignment is what creates premium pricing. AI can accelerate this significantly: identifying companies with adjacent capabilities, flagging acquirers who have done similar deals in the past and scoring the potential fit between a buyer's stated strategy and the seller's profile. It doesn't replace judgment, but it turns what used to be a manual, relationship-dependent process into something more systematic - and in doing so, it surfaces buyers that a traditional outreach process would have missed entirely.

Why you should not anchor your valuation expectations early

One of the most counterintuitive pieces of advice in M&A: don't decide what your company is worth before the market tells you.

Founders often come into a process with a number in mind - based on a competitor's reported exit, a rule-of-thumb multiple, or what they need to hit a personal financial target. The problem with anchoring to that number is that it kills price discovery.

Say that you think your company costs $10m in Enterprise Value. If you go to market communicating that number you will scare off interested buyers that are willing to offer anything below that number. The ones that are willing to give more will just come back with numbers around the $10m, while they might've otherwise offered a lot more.

It could also distort your decision-making in ways that cost you money. If your anchor is too high, you reject reasonable offers and drag out the process - sometimes fatally. If your anchor is too low, you accept the first offer that clears your threshold without testing whether the market would have paid more.

The better approach is to let the process generate the valuation. Build the narrative, prepare the materials, run a competitive process, and let the offers tell you what the market is willing to pay. Your job isn't to set the price - it's to create the conditions under which the highest credible price emerges.

This doesn't mean you should have no sense of valuation ranges. Understanding where comparable businesses trade - in terms of EBITDA multiples, revenue multiples, and deal structures - is essential context. But there's a difference between having context and having an anchor. Context helps you evaluate offers intelligently. An anchor makes you rigid.

What happens during due diligence

Once you sign an LOI and grant exclusivity to a buyer, the diligence phase begins. This is where the buyer (and their advisors, lenders, and insurers) verify everything you've represented about the business.

For SMB transactions, diligence typically runs 30 to 60 days - though it can extend significantly if the seller isn't prepared or if issues surface that require resolution. Here's what most founders underestimate about diligence: it's not a formality and many deals die at this phase of the process.

The issues that most commonly derail SMB deals during due dilligence

Based on recent data from broken-deal analyses, insurance claims studies and transaction advisory reports, the issues that most frequently cause price reductions, deal restructurings, or outright failures in SMB transactions cluster into a few categories.

Earnings quality problems remain the most common trigger. When a buyer's quality-of-earnings review produces an adjusted EBITDA that's materially below the seller's representation, the deal either reprices or collapses. This is especially acute in SMBs where accounting infrastructure tends to be lighter - QuickBooks-based bookkeeping, limited audit trails, and owner-operators managing the finance function alongside everything else.

Customer concentration is the second most common red flag. If 30% or more of revenue depends on a single client - or if key customer contracts contain change-of-control termination clauses - buyers either walk, demand earnouts, or significantly haircut the price. This is one area where early preparation pays off enormously: if you know concentration is a risk, building diversification and documenting retention rates before going to market changes the conversation entirely.

Tax exposures are particularly consequential in European deals. Data from Euclid Transactional's claims studies shows that in EMEA, tax-related claims represent around 38% of warranty and indemnity insurance claims received - more than double the rate in North America. Common issues include unfiled or incorrectly filed returns, VAT mistakes, payroll tax misclassification, and cross-border permanent establishment risks.

Legal and compliance gaps round out the highest-risk category. Missing licenses, undisclosed litigation, data protection non-compliance and regulatory exposure in specialized verticals. Industry reports show that non-quality-of-earnings diligence findings (which include legal, compliance and contract issues) were one of the largest causes of unsuccessful deals in 2025 - around 1 in 4.

How to survive diligence without losing your price

The principle is simple even if the execution takes discipline: disclose proactively, respond quickly, and never let the buyer discover something you already knew about.

When a buyer finds a problem you didn't flag, two things happen simultaneously. The problem itself becomes a negotiation point (price reduction, escrow, indemnity). And the buyer's trust in everything else you've told them erodes - which makes every subsequent finding worse.

The sellers who navigate diligence cleanly tend to share a few traits: they've done their own pre-diligence, their data room is organized and complete before the LOI is signed, and they respond to information requests within 24 to 48 hours rather than letting them stack up.

How long does it really take to sell an SMB?

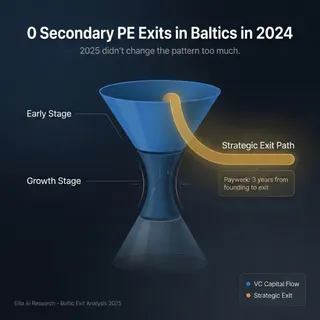

For most SMBs in the EUR 1M to 20M enterprise value range, the realistic timeline from engaging an advisor to closing is 3 to 6 months. Data from IBBA/M&A Source's 2025 market pulse shows months-to-close in the lower middle market ranging from roughly 6 to 11 months including the preparation phase, but the AI-native process can significantly decrease this timeline.

Here's how that time typically breaks down during an AI-native M&A process:

Two things consistently extend timelines beyond this range. The first is seller readiness - if you're building the data room during diligence or don't delegate sufficient time for the process, every phase takes longer. The second is deal complexity that wasn't anticipated: regulatory approvals, customer consents with change-of-control provisions, financing conditions that introduce a third party's timeline into your process and so on.

Cross-border transactions add additional time and can be a bit longer, driven by jurisdictional complexity, tax structuring and regulatory approvals.

What about going it alone? The case for (and limits of) selling without an advisor

Some founders consider running the sale process themselves, particularly if they already have a relationship with a potential buyer. This can work in narrow circumstances - typically when the buyer is well-known to the seller, the business is straightforward, and the founder has significant transaction experience.

But for most first-time sellers, the economics favor having professional support. Not because founders aren't smart enough to negotiate, but because the process requires sustained, parallel-track execution across legal, financial, and commercial workstreams over several months - while you're still running the business. An advisor enables you to create competitive tension easier which then leads to around 25% higher valuations according to research.

The counterargument - that advisory fees are significant is fair. But that cost needs to be weighed against what a well-run competitive process adds in purchase price uplift, deal certainty and founder sanity. Additionally, at Eilla - we only charge a success fee upon the successful closing of the deal to align our incentives with the company and decrease the risk if the deal doesn't close.

Common mistakes that destroy value during an SMB sale

Beyond the process mechanics, certain patterns consistently cost sellers money across hundreds of observed transactions.

Treating diligence as adversarial rather than collaborative. Buyers expect to find issues - no business is perfect. What kills deals isn't the issue itself; it's the seller's response. Defensiveness, delayed responses, and selective transparency erode trust faster than any financial finding. The sellers who protect their price during diligence are the ones who address problems head-on and offer solutions rather than excuses.

Accepting an NBO based on headline price without scrutinizing structure. A EUR 10M offer with a EUR 3M earnout, aggressive working capital targets, and 12 months of exclusivity is a fundamentally different deal than a EUR 9M all-cash offer with 60 days to close. The headline number is not the number.

Ignoring the closing mechanics until they become the critical path. Third-party consents (for example key customers), payoff letters for existing debt, and employment agreements for key staff all take time. When these aren't started early, they become the reason a deal that's substantively done takes an extra two months to actually close.

A framework for evaluating whether you're ready to sell

Before entering a process, pressure-test three questions that map directly to the most common failure modes:

Can your EBITDA survive a quality-of-earnings review without material adjustments? If the answer is uncertain, you're exposed to the single largest post-LOI deal-killer. Get a sell-side QoE done first, fix what you can, and price what you can't fix into your expectations.

Do you know your risk inventory - and can you disclose it on your terms? Tax exposures, customer concentration, contract assignability, compliance gaps, key-person dependencies. If a buyer is going to find it anyway (and they will), you're better off disclosing it proactively than having it surface as a "discovery" during diligence.

Are all decision-makers aligned on price, structure, timeline, and post-close expectations? Misalignment between co-founders, between founders and their families, or between what a founder wants and what the market will bear is responsible for more broken deals than any buyer behavior.

If you can answer yes to all three, you're in a strong position to run a process. If you can't, the time spent getting to yes is almost always worth more than the time spent trying to sell before you're ready.

Key takeaways

- Selling an SMB typically takes 3 to 6 months from go-to-market to close, but it can extend more depending on the complexities of a deal. An AI-native approach accelerates this process and decreases the timeline.

- The narrative you build around your business - how it's positioned, what story the numbers tell - matters as much as the numbers themselves in determining what buyers are willing to pay.

- A competitive process with multiple qualified buyers consistently produces better outcomes than bilateral negotiations, because competitive tension protects your price through every phase of the deal. But competitive tension starts with outreach - the broader and more targeted your buyer universe, the more likely you are to find the acquirer whose strategy makes your business worth a premium.

- For SMBs, the strategic buyer universe is large but opaque. Unlike large-cap deals where the likely acquirers are well known, SMB sellers often don't know which companies might be a fit - and neither do many traditional advisors. Systematic, AI-assisted buyer identification can surface acquirers that a relationship-driven process would miss entirely.

- Anchoring to a specific valuation before the market has spoken distorts decision-making; let the process generate the price, and use comparable data as context rather than a target.

- Due diligence is where a lot of SMB deals fall apart - with quality-of-earnings gaps and undisclosed legal or compliance issues accounting for nearly half of confirmatory DD failures.

- Financial preparation (clean EBITDA, organized data room, proactive disclosure of known risks) is one of the highest ROI activities a seller can undertake before going to market.

- The structure of an offer - earnout terms, working capital targets, exclusivity length - often matters more than the headline price.

Frequently asked questions

How long does it take to sell a small business? Most SMB sales take 3 to 6 months from active marketing to close. Deals can stretch to 9 to 12 months depending on seller preparation, deal complexity, regulatory and financing conditions. An AI-native process can support every stage of the process from preparing the marketing materials, through buyer identification and outreach to the DD and closure of the deal, which significantly decreases the timeline.

What is a competitive M&A process and why does it matter for SMBs? A competitive process involves approaching multiple qualified buyers simultaneously under a structured timeline, creating competitive tension that drives better pricing and terms. For SMBs, this is particularly important because bilateral (single-buyer) negotiations give the buyer disproportionate leverage on price, timing and re-trading during diligence.

How do you find the right buyers when selling a small business? The buyer universe for an SMB is typically much larger than founders expect - but also much harder to map. Strategic buyers could include companies in your space, adjacent verticals or even different industries looking to acquire a specific capability. A strong outreach process starts by building a broad list of high-fit targets, scoring them based on strategic alignment and then approaching them systematically under NDA. AI can accelerate this by identifying companies with complementary capabilities, flagging acquirers who have completed similar transactions, and calculating the potential fit between a buyer's strategy and the seller's profile - surfacing opportunities that a purely relationship-based approach would miss.

What are the most common reasons SMB deals fall apart durind DD? Based on recent broken-deal data, the top causes are quality-of-earnings discrepancies (the buyer's EBITDA number doesn't match the seller's), non-financial diligence findings (legal, compliance, contract, or customer issues), and renegotiation breakdowns. Together, these account for over 60% of DD deal failures in lower-middle-market transactions.

What is a non-binding offer in M&A and what should it include? A non-binding offer (NBO) is the formal expression of interest a buyer submits after completing their commercial due diligence - typically after reviewing the CIM and going through a management presentation. It should include a valuation range or specific price, proposed deal structure (cash, earnout, rollover equity), key conditions and a timeline for completing confirmatory due diligence. Non-binding means neither party is legally committed at this stage, but it sets the framework for negotiating exclusivity and moving toward a binding agreement.

How do I value my SMB for a sale? SMB valuations are depend on the industry typically expressed as a multiple of adjusted EBITDA, with multiples varying by industry, size, growth profile, and market conditions. For tech start-ups with high growth potential, metrics such as annual recurring revenue (ARR) and net revenue retention (NRR) can also be key metrics that would impact valuation significantly. Rather than anchoring to a specific multiple, the most effective approach is to build a strong information package, run a competitive process, and let buyer offers reveal what the market will actually pay - while using comparable transaction data as context for evaluating those offers.

If you're considering selling your company and want to understand what a well-structured M&A process could look like for your specific situation, our advisory team is happy to walk through it with you - no commitment required.

Are you considering an exit?

Meet one of our M&A advisors and find out how our AI-native process can work for you.